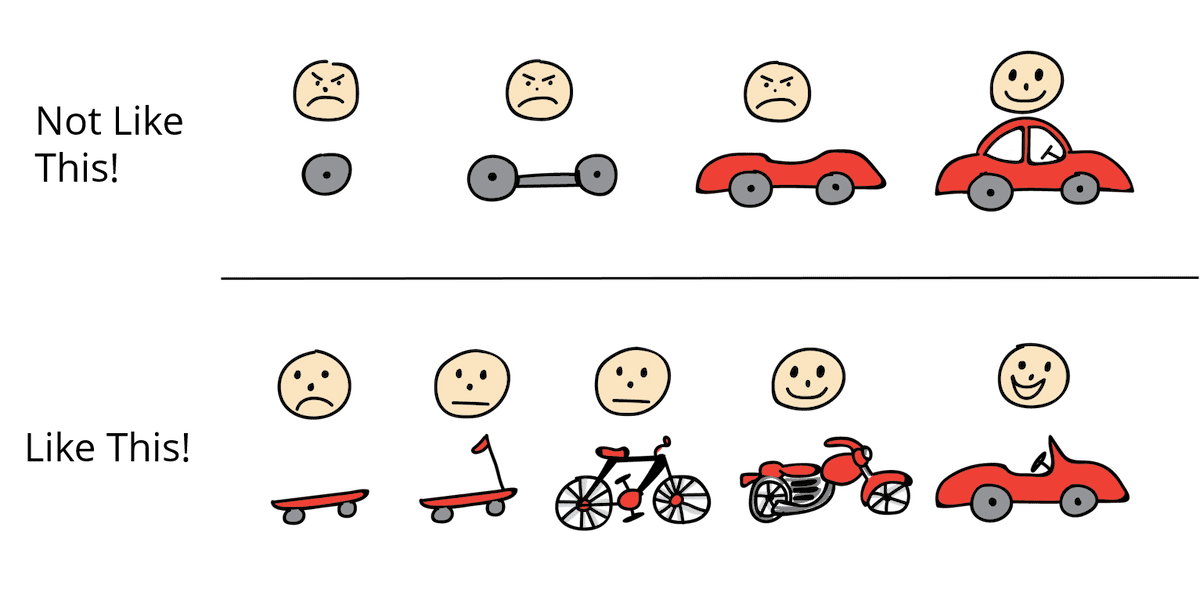

I have a love-hate relationship with “the MVP car”, that classic illustration that shows us the RIGHT and WRONG way to build a product. To be fair, I don’t think its creator Henrik Kniberg would want it called “the MVP car” at all. According to his post the whole point of the illustration is to replace “MVP” with something more descriptive like “Earliest Testable/Usable/Lovable Product”. I wholeheartedly agree with the notion and short-cycle iteration beats long-cycle “Bing Bang Delivery” as Kniberg refers to it.

Kniberg notes that sharing the car like a meme erases his original context and all we see is the car. Despite taking the time to get the context and being a lover of iteration, I think I have built up petty grievances over the years with the MVP car. The next thousand or so words are about those disagreements.

First off, skateboards are rad. That should be a happy face.

My first real issue is that the wheel → chassis → convertible → car is way closer to the way you actually build a car from an industrialized manufacturing perspective. Henry Ford didn’t put skateboards into the factory and poop out cars. Ford’s factories started with wheels and pre-fabricated chassis and transformed them into consumer vehicles through a process of craftsman-level precision and heaps of welding and stitching. This is still the same process car manufacturers use today but with robots and giga-presses. Most product organizations need to develop a predictable process for pushing work through the system.

Next grievance! Apart from the bike → motorcycle evolution, the skateboard → scooter → bike → motorcycle → convertible path is not how any of these products evolved. They evolved over literal centuries and millennia through repeated processes of invention and miniaturization/optimization. If we’re trying to be accurate, between the bike and the motorcycle, you probably need a steam ship with an apartment complex-sized engine room. A lot of products follow a simple formula: Take thing that exists and bolt on new technology.

One thing the MVP car does well is that it lets you imagine alternate routes on how you might evolve the complexity of a feature over time while delivering something usable the whole way through. Kniberg is right about learning too. By reducing scope and “following the fun” you might find customers strongly prefer one idea over another. Instead of “one big release” you mature your idea over time with happy customers along the way. But that leads me to the next handful of issues I have with the MVP car.

In the MVP car analogy, you have to know where you’re going. You have to have a clear idea of the end state and work a plan backwards from there to deliver something over time. It’s like how you write a murder mystery in reverse. This process works great if you’re building something that’s a known quantity but “know where you’re going” works less great for exploratory or emergent work. The wheel → chassis → convertible → car flow is a more realistic product evolution; a cobbling together of existing technologies, then adding features to make it more user-friendly (like a steering wheel).

With the MVP car, there’s also Theranos-levels of risk in over-promising to management and investors. You’ve already sold the idea in PowerPoints and Figma without technical constraints and now they signed-off on it. We’re a car company, does anyone here even know how to make good UI a skateboard? Can we even source wood? There’s now downward pressure to deliver on a predetermined timeline and no opportunity to pivot to a rickshaw or a tuk-tuk instead of a car because any divergence is a mission failure.

It takes specific skills to pull off an MVP car. It takes people who have built up a specific kind of innate muscle memory. It takes a team composition that has a mix of people with high and low standards. Not too high that nothing ever ships, but not too low that garbage goes out the door. People who can intuit around what is essential, who can kill their darlings, and people who can answer the question “Given the timeframe, what does this need to be right now?”

The MVP car intends to be customer focused… but is it though? Have you ever done a redesign? Bosses question them and audiences universally hate them even if it’s 10,000x better. They cost a fortune and customers complain you’ve inconvenienced their lives with this new direction. Smaller, imperceptible iteration tends to sail through the gauntlet a lot smoother. And we want to move fast and have five major iterations of our product? That’s a hard sell both internally and externally. I can already hear engineering departments saying they’d rather not build five different vehicles, they’d rather build one vehicle once. A codebase with five apps turducken’d inside is going to be difficult to work in unless a lot of planning went into it from the start.

The biggest issue I have is that there’s no tactical or practical advice contained within the MVP car other than “break your goal down into five separate modes of transportation of increasing difficulty to build.” The advice is so general and non-specific that it’s almost meaningless. I get that Kniberg’s goal was to be vague but exciting… but as a foundation to build your castle on, it’s hard to grab hold. The absence of a process is also a process and creates a void where people fill it with a lot of strange ideas.

As I said, I think there’s value in the MVP car’s premise that it’s best to iterate forward to a goal. I think it’s important to find what makes your product good and focus on the essential pieces. Do you know what fits within the spirit of the MVP car without rebuilding the customer-facing app five times? A way to evolve an idea with customers before you get there? A tool that helps you see and feel the end goal before you commit? A tangible artifact that gives a discussion point for breaking an job down into deliverable phases? That’s right… prototypes. And notably, in Kniberg’s post three of the four case studies talk about sharing prototypes or rough versions of ideas with customers.

In conclusion, those are my beefs with the MVP car. It’s actually a fine analogy, inspiring even, but this list has been building for years and it feels good to get it all out there. Ironically, the last line of Kniberg’s post about the MVP car is this:

And remember – the skateboard/car drawing is just a metaphor. Don’t take it too literally :o)

Oops.