One unsung feature in the web components space that I don’t think gets enough attention is the Custom Elements Manifest initiative. I think it’s the killer feature of web components.

Known as “CEM” to its friends, a CEM is a community standard JSON format that surfaces information about your component APIs. The analyzer scans your class-based component to build up a “manifest” of all the methods, events, slots, parts, tag name, and CSS variables you want to expose. It works on a single component or an entire system’s worth of components. If you want to surface more details to consumers (like accepted attributes or CSS custom properties), you can provide more context to the analyzer through JSDoc comments and/or TypeScript types – which is good code hygiene and a favor for your future self anyhow. Here’s an example from the playground:

/**

* @attr {boolean} disabled - disables the element

* @attribute {string} foo - description for foo

*

* @csspart bar - Styles the color of bar

*

* @slot - This is a default/unnamed slot

* @slot container - You can put some elements here

*

* @cssprop --text-color - Controls the color of foo

* @cssproperty [--background-color=red] - Controls the color of bar

*

* @prop {boolean} prop1 - some description

* @property {number} prop2 - some description

*

* @fires custom-event - some description for custom-event

* @fires {Event} typed-event - some description for typed-event

* @event {CustomEvent} typed-custom-event - some description for typed-custom-event

*

* @summary This is MyElement

*

* @tag my-element

* @tagname my-element

*/

class MyElement extends HTMLElement {}

The JSDoc notation is forgiving (it supports both @cssprop and @cssproperty) and with the ability to document your ::part() and <slot> APIs, it’s more descriptive than what you’d get with a basic TypeScript interface. Eagle-eyed observers will notice there’s a distinction made between an @attribute and an @property, that’s because those are different concepts in HTML, ergo different in Custom Elements. Attributes (strings, numbers, booleans) tend to reflect, properties don’t.

After that thin layer of documentation, it’s a two-liner to generate the manifest:

npm i -D @custom-elements-manifest/analyzer

cem analyze

This will generate a file called custom-elements.json in your package directory.

View Sample Output

{

"schemaVersion": "1.0.0",

"readme": "",

"modules": [

{

"kind": "javascript-module",

"path": "src/my-element.js",

"declarations": [

{

"kind": "class",

"description": "",

"name": "MyElement",

"cssProperties": [

{

"description": "Controls the color of foo",

"name": "--text-color"

},

{

"description": "Controls the color of bar",

"name": "--background-color",

"default": "red"

}

],

"cssParts": [

{

"description": "Styles the color of bar",

"name": "bar"

}

],

"slots": [

{

"description": "This is a default/unnamed slot",

"name": ""

},

{

"description": "You can put some elements here",

"name": "container"

}

],

"members": [

{

"kind": "field",

"name": "disabled"

},

{

"kind": "method",

"name": "fire"

},

{

"type": {

"text": "boolean"

},

"description": "some description",

"name": "prop1",

"kind": "field"

},

{

"type": {

"text": "number"

},

"description": "some description",

"name": "prop2",

"kind": "field"

}

],

"events": [

{

"name": "disabled-changed",

"type": {

"text": "Event"

}

},

{

"description": "some description for custom-event",

"name": "custom-event"

},

{

"type": {

"text": "Event"

},

"description": "some description for typed-event",

"name": "typed-event"

},

{

"type": {

"text": "CustomEvent"

},

"description": "some description for typed-custom-event",

"name": "typed-custom-event"

}

],

"attributes": [

{

"name": "disabled",

"type": {

"text": "boolean"

},

"description": "disables the element"

},

{

"type": {

"text": "string"

},

"description": "description for foo",

"name": "foo"

}

],

"superclass": {

"name": "HTMLElement"

},

"tagName": "my-element",

"customElement": true,

"summary": "This is MyElement"

}

],

"exports": [

{

"kind": "custom-element-definition",

"name": "my-element",

"declaration": {

"name": "MyElement",

"module": "src/my-element.js"

}

}

]

}

]

}

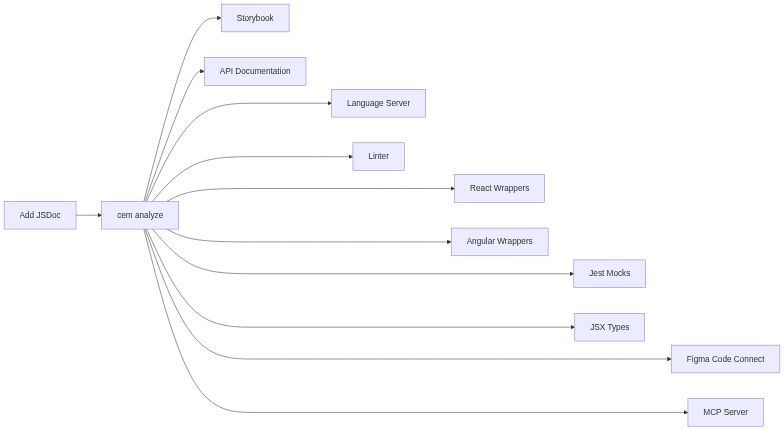

API extraction through TypeScript or JSDoc isn’t a novel concept, but what I find novel is the community tooling built around it. With a Custom Element Manifest, community plugins can use that information to generate files, populate dropdowns, add red squiggles, provide autocomplete, and automate a lot of the mundane meta-system DX work that comes with supporting a component library:

- API Documentation - Your CEM can power your readme.md and component-level documentation.

- Storybook - Using the Storybook plugin you can use your CEM to automate the generation of your Storybook stories.

- Language Servers - It can be frustrating to not have your editor recognize the HTML you invented. CEM-powered language servers solve that issue. A few options here.

- Linter - Want to lint HTML before shipping? CEM can power this.

- React Wrappers - React 19 supports web components, but if you’re trying to use web components in a React <= 18 project, you’ll need little wrapper shims. Creating these by hand isn’t fun and we can hand this work off to the CEM.

- Other Framework Wrappers - Shims for SolidJS, Svelte, and Vue.js.

- JSX Types - JSX isn’t happy unless you add new interfaces to the JSX namespace. CEM can generate this for you.

- Jest Mocks - If you’re still using Jest in the year of our lord 2025, I feel bad for you but there are plenty of people in this situation. Jest hates Custom Elements because Custom Elements are real DOM and not VDOM. No plugin to link to (sorry!) but I have seen teams using CEM to generate Jest mocks to smooth over the process when integrating with legacy testing solutions.

- Figma Code Connect - If you want to connect your web components to Figma, you can automate that as well.

- MCP Server - If you want to give your AI Agents insights into the components available in the current project, you can install an MCP Server that parses your CEM. (Couple options here)

Burton Smith who runs WC Toolkit has been helping us roll out some of our CEM work and we’re starting to turn some of these capabilities on. One pain point I’m hoping to solve is too much boilerplate. We have a lot of files in our individual component packages to power assorted tasks and integrations and I can see a world where we generate nearly all our readmes, storybooks, and even some low-level test coverage from the CEM at build-time or run-time.

From a single file we get the following outcomes…

- Spend less time/energy maintaining and schlepping boilerplate code

- Improve baseline test coverage and make it more predictable

- Make new components easier to create, ideally speeding up development

- Reduce cognitive overhead when jumping into the project

- Provide a forcing function for more/better documentation

- Potentially improve the design-developer bridge through Figma Code Connect and MCPs

Again, I want to applaud the web components community here. There’s no VC-funded corporate overlord roadmap driving the Custom Elements Manifest initiative, just fellow enthusiasts. From a community perspective, that’s a positive signal for me. Adding it to your project is low-effort, high-impact type work and I probably only covered about a quarter of what a CEM can do for you, which goes to show a community agreeing on a standardized way to describe components is a powerful tool.