My wife and I have noticed that whenever we make coffee, it’s completely different despite the fact we use the same grounds, the same filters, the same coffee maker, the same water faucet, and the same measuring devices. We were both stunned that the flavor of our morning brew depended so drastically on who volunteered to make it. At first, it seemed that the only difference was the person twisting the knob on the coffee maker.

Over time, I started to notice subtle differences in our approach. My wife used filtered water, I used tap. My wife would short the coffee maker about a half cup of water, I’d add an extra half cup. She used more free-form heaping scoops, I tend to divvy out a more exact 1:1 tbsp-to-cup ratio.

I started referring to this as “the invisible hand of the barista”, the quality and feel of a product is directly affected by micro-decisions of those involved in making it. It can make or break a product.

I think this affects other service industries as well; the bartender who prepares your drink just the way you like it, the music producer who only prints solid gold records, or the feel of a house drafted by an experienced architect. I think it even extends to the websites and software products you and I build.

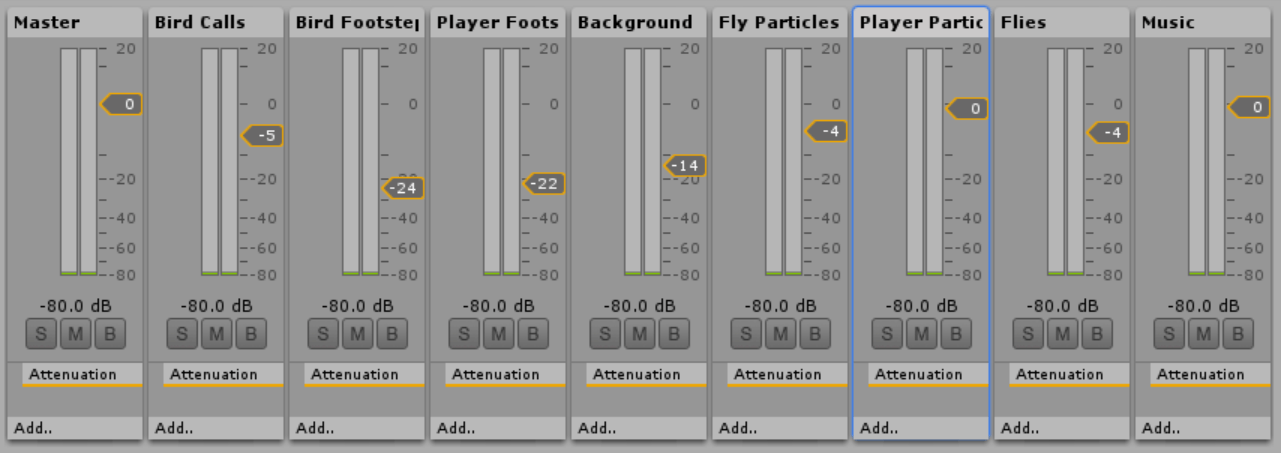

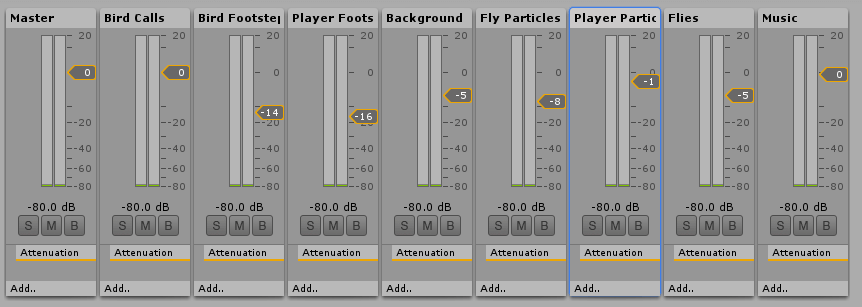

I noticed this phenomenon in another context recently while making a video game following a Treehouse course. For the final portion of the course you add sounds to your game to make it come alive. The instructor, Nick Pettit, made the following choices…

And here’s my mix…

Same game, two subtly different auto mixes, two different atmospheres. While some of the difference is audio mixing skill and knowing best practices, the final output mostly comes down to personal taste. With some subtle changes in lighting and color balance, it could look like a different game entirely.

Controlling variance

Maybe variance is not what you or your product want. Quality can be controlled, it just requires agreed upon standards, mechanical automation, and proper training.

Using standard measurements for a shot of espresso and a shared lexicon for what constitutes light, dark, and medium blend coffee goes a long way in preserving tradition and meeting customer expectations.

Any Aeropress or Chemex aficionado will swear by an electric kettle to control temperature. Controlling a major variable like temperature makes a predictable cup of coffee so you can better experience the flavor of your organic, ethically-sourced, locally-roasted beans.

If machines fail to control variance, training humans is necessary to bring skill to a higher level. Some tasks might have a prerequisite level of education or achievement. Sometimes a skill can be taught and improved. My favorite example of this is from 2008, noticing a slip in quality, Starbucks closed all of their 7,100 stores for 3.5 hours to train baristas. A massive investment into the quality of their product.

Osusume

In Japan there is there is this concept of “Osusume” (おすすめ). On a literal level it means “your recommendation”, but when you ask a skilled chef for “Osusume”, you are putting your dining experience in their hands with little regard for cost. I liken it to saying “I trust your skill and expertise to design the perfect dining experience for me.”

Sometimes the chef will base their choice on special ingredients available that day. Sometimes the choice is based on what the chef knows about your personal likes and dislikes. If the chef’s specially prepared dish does not meet expectation, a small amount of shame is shared. The inability to describe and the inability to infer.

I don’t know where I’m going with this, other than I think it’s important to have baristas in various areas of your life. People whose taste and expertise you trust that will guide you to new and better experiences.